- California wildfire burns out of control but firefighters could get a break when winds diminish

- 'Flooding is our number one natural disaster' | Breaking down the voter-approved Harris County Flood Control District tax rate hike

- Powerful Category 3 Hurricane Rafael knocks out power in Cuba as it heads to the island

- NC Forest Service warns of increased wildfire risk in western part of state after Helene

- First responders searched for hours after being told two people were swept away in flash flood

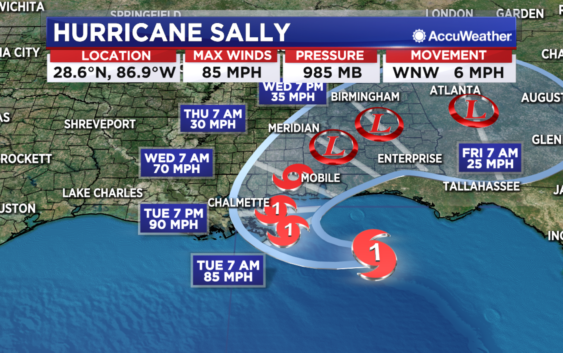

Hurricane Sally, now a Category 2, threatens Gulf Coast with a slow drenching

The storm was on a track to brush by the southeastern tip of Louisiana and then blow ashore late Tuesday or early Wednesday near the Mississippi-Alabama state line for what could be a long, slow and ruinous drenching.

Storm-weary Gulf Coast residents rushed to buy bottled water and other supplies ahead of the hurricane, which powered up to a Category 2 in the afternoon, with further strengthening expected.

Jeremy Burke lifted things off the floor in case of flooding in his Bay Books bookstore in the Old Town neighborhood of Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, a popular weekend getaway from New Orleans, about 60 miles to the west. The streets outside were emptying fast.

“It’s turning into a ghost town,” he said. “Everybody’s biggest fear is the storm surge, and the worst possible scenario being that it just stalls out. That would be a dicey situation for everybody.”

Sally has lots of company during what has become one of the busiest hurricane seasons in history – so busy that forecasters have almost run through the alphabet of names with 2 1/2 months still to go.

For only the second time on record, forecasters said, five tropical cyclones were swirling simultaneously in the Atlantic basin. The last time that happened was in 1971.

In addition to Sally were Hurricane Paulette, which passed over a well-fortified Bermuda on Monday and was expected to peel harmlessly out into the North Atlantic, and Tropical Storms Rene, Teddy and Vicky, all of them out at sea and unlikely to threaten land this week, if at all.

As of late afternoon, Sally was about 145 miles southeast of Biloxi, Mississippi, moving at 6 mph.

Sally’s sluggish pace could give it more time to drench the Mississippi Delta with rain and push storm surge ashore.

People in New Orleans watched the storm’s track intently. A more easterly course could bring torrential rain and damaging winds to Mississippi. A more westerly track would pose another test for the low-lying city, where heavy rains have to be pumped out through a century-old drainage system.

Even with a push toward the east, New Orleans, which is on Lake Pontchartain, will be in the storm surge area, said University of Miami hurricane researcher Brian McNoldy. He said New Orleans “should be very concerned in terms of track.”

The National Hurricane Center forecast storm surges of up to 11 feet, including 4 to 6 feet in Lake Pontchartrain and 6 feet in downtown Mobile, Alabama.

In eastern New Orleans, drainage canals were lowered in anticipation of torrential rains, Mayor LaToya Cantrell said. New Orleans police went on 12-hour shifts, and rescue boats, barricades, backup generators and other equipment were readied, Police Superintendent Shaun Ferguson said.

In coastal Mississippi, water spilled onto roads, lawns and docks well before the storm’s arrival. Sally was expected to bring a surge of 10 feet or more.

The town of Kiln, Mississippi, where many homes sit high on stilts along the Jourdan River and its tributaries, was under a mandatory evacuation order, and it appeared most residents obeyed. Many of them moved their cars and boats to higher ground before clearing out.

Michael “Mac” Mclaughlin, a 72-year-old retiree who moved to Kiln a year ago, hooked his boat up to his pickup truck to take to his son’s house in another part of Mississippi before heading to New Orleans to ride out Sally there with his girlfriend.

“It would be dumb to stay here,” Mclaughlin said. He said his home was built in 2014 to withstand hurricanes, “but I just don’t want to be here when the water’s that deep and be stranded. That wouldn’t be smart.”

In the Venetian Isles section of eastern New Orleans, Willie Harris, a meter reader for the city, said he was on standby for clearing drains to prevent backups that could cause flooding. He said he and his fiancee had plenty of food and water and would ride out the hurricane at home. Some residents parked their cars on their lawns in a sure sign a storm was expected.

On Aug. 27, Hurricane Laura blow ashore in southwestern Louisiana along the Texas line, well west of New Orleans, tearing off roofs and leaving large parts of the city of Lake Charles uninhabitable. The storm was blamed for 32 deaths in the two states, the vast majority of them in Louisiana.

More than 2,000 evacuees from Hurricane Laura remain sheltered in Louisiana, most of them in New Orleans-area hotels, Gov. John Bel Edwards said.

The extraordinarily busy hurricane season – like the catastrophic wildfire season on the West Coast – has focused attention on the role of climate change.

Scientists say global warming is making the strongest of hurricanes, those with wind speeds of 110 mph or more, even stronger. Also, warmer air holds more moisture, making storms rainier, and rising seas from global warming make storm surges higher and more damaging.

In addition, scientists have been seeing tropical storms and hurricanes slow down once they hit the United States by about 17% since 1900, and that gives them the opportunity to unload more rain over one place, like 2017’s Hurricane Harvey in Houston.

In Mississippi, Gov. Tate Reeves said Sally could dump up to 20 inches of rain on the southern part of the state. Shelters opened, but officials urged people who are evacuating to stay with friends or relatives or in hotels, if possible, because of the coronavirus.

People in shelters will be required to wear masks and other protective equipment, authorities said.

“Planning for a Cat 1 or Cat 2 hurricane is always complicated,” Reeves said. “Planning for it during 2020 and the life of COVID makes it even more challenging.”

In Alabama, Gov. Kay Ivey closed beaches and called for evacuations.

—

Associated Press reporters Rebecca Santana in New Orleans; Seth Borenstein in Kensington, Maryland; Emily Wagster Pettus and Leah Willingham, in Jackson, Mississippi; and Jeff Martin in Marietta, Georgia, contributed to this story.

Copyright © 2020 by The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved.